The Arctic is a Crowded Place

Saturday August 2, 2014 (72o 58’N, 76o 17’W): Dundas Harbor

Having decided that Pond Inlet was not a viable refueling stop, the next logical choice was to head north to Lancaster Sound, the entrance to Parry Channel and common waters for all routes through the Northwest Passage. Conceivably, we had enough fuel to make it all the way to Gjoa, which is nearly halfway through to Alaska. However, for that to succeed that would require more sailing and less motoring than we’ve been able to manage so far. Plus, there is no guarantee that the approach to Gjoa would be ice free when we got there. A more conservative approach is to refuel at Resolute, which is approximately halfway to Gjoa, but nearly 100 miles out of the way. In a sailboat, one hundred miles is a long detour. Either way, heading to Lancaster Sound was the next step, so as soon as the winds were favorable, we motored out of our Bylot Island anchorage, raised sails, and turned towards Dundas Harbor, 135 miles to the north.

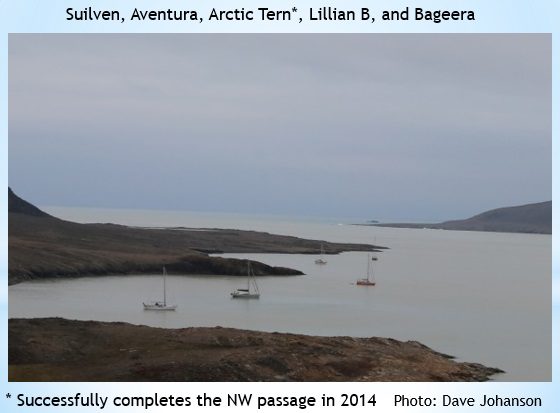

We selected Dundas Harbour based on recommendations from various sources, but also because John Ellis of The Blue Planet Odyssey had e-mailed that the yachts Adventura and Suilven were anchored there. Adventura is captained by Jimmy Cornell, author of “World Cruising Routes,” and Suilven is the yacht of John and Linda Andrews, who have joined Cornell in his first attempt to sail the Northwest Passage. Given this implicit recommendation, plus the potential to meet and exchange information should they still be at Dundas, we entered its coordinates into the GPS and set a course. While the fog returned as soon as we left Bylot, the winds would be favorable the entire crossing. Initially they were light and from dead astern. Traveling in the same direction as the wind may sound optimal, but when the winds are light and from behind, it is difficult to keep the sails full and steady. The mainsail is easily filled, but if the foresail is on the same side of the boat, it hangs in the shadow of the main. If the wind is directly astern, the sails can be configured on opposite sides, or “ wing and wing”, but if there are waves of any consequence, the weight of the foresail can cause it to repeatedly deflate and then refill with a resounding crack, loosing efficiency and grating on the nerves of anyone within earshot. The best solution is to fly a spinnaker, which is a lightweight billowing sail deployed ahead of the bow, like the inflated chest of a frigate bird. Similar to flying a kite, the spinnaker is a temperamental sail that requires some effort to hoist and tends to get wrapped up in itself if the wind shifts. But once flying, a spinnaker is both effective and beautiful. And, for nine hours early in the crossing, the spinnaker was flying proudly, quietly generating 5 to 6 knots of speed through the water driven by only 12 knots of wind. As the winds clocked from south to west, the spinnaker was replaced by the genoa, and our tack changed from a dead run to close haul over the 135 mile trip. Only for final 10 miles into the harbor did we motor, as by then the wind had come around to blow directly on our nose. At the same time we entered Dundas Harbour, another yacht was entering from the west.

Once inside, Dave steered towards a protected looking spot and did a “dance” with the Forward Looking Sonar (FLS) to scope out the depths and make sure there were no hidden obstructions. After circling around, he turned into what little wind there was behind a spit of land and Pete dropped anchor in about 20 feet of water. A quarter mile away, the other yacht was doing the same. Fifteen minutes later they hailed us and we learned that it Suilven. They were returning to Dundas after a harrowing and unsuccessful 36 hour attempt to refuel at Artic Bay to the south, having had to deal with regions of 90 percent ice. With a crew of three, they sounded exhausted, so we bid them good night. The next morning, Adventura had joined them, after having also tried unsuccessfully for Arctic Bay. Since there are a limited number of harbors along the way, it is not unexpected that we would have company. We have had at least one other boat at every port or anchorage since leaving Maine. Now there were three yachts in Dundas Harbour. By the morning of the next day, our friends from Nuuk, Arctic Tern, arrived followed by the Dutch boat Bagheera, bringing the total to five. Les of Arctic Tern said the vessel Drina was also on her way and by late afternoon, she had dropped anchor as well.

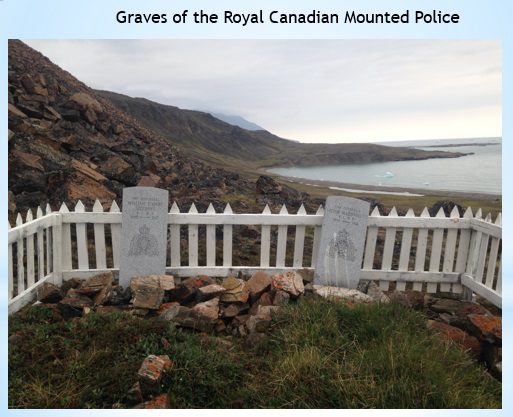

As in Nuuk, we visited with Ali, Les and Randall on Arctic Tern, enjoying their company and gaining valuable advice in the process. I also rowed over and introduced myself to John, Linda and crew member Max on board Suilven, exchanging weather and contact information as well. Later Pete and I had the opportunity to meet six of the eight crew members on board Adventura along with Les, Ali, Randall, Linda and Max in an absurdly unlikely social event as landing parties from four boats, shotguns in hand, happened to converge on top of a barren hillside overlooking the abandon four building settlement of Dundas Harbor. The initial contact resembled an impromptu reception line as everyone exchanged first names and boat connections. Of the six boats at anchor, all but Bagheera have plans to attempt the Northwest Passage. Ali had a list of a dozen others who are attempting it as well. Despite the typically independent nature of sailors, there is an inevitable common ground when you meet someone at latitude 74 N, symbolized in a sense by the desolate hill near the graves of Dundas Harbour.