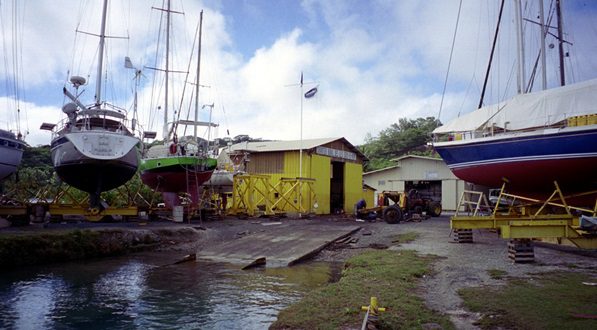

Chantier Naval Des Isles

Friday July 9, 2004

Bora Bora, French Polynesia

S 16o 29.332’, W 151o 45.707’

On our way to the popular French Polynesian resort island of Bora Bora, we needed to make a quick stop at the shipyard, Chantier Naval des Iles (CNI), on the island of Raiatea to order a new shroud. The shrouds are the side support cables for the mast and Peter had discovered that one of them had broken strands. While strong enough for a short sail, it would need to be replaced before leaving on the long crossing to Hawaii. Our hope was to have a new one ordered and delivered while we were enjoying Bora Bora. Such was not to be the case.

As Lillian motored around the northern point of Raiatea enroute to the shipyard, we saw a small boat off to port, with a man standing amidship waving both arms over his head like a bird trying to take off. For an instant, it looked as if he were enthusiastically waving hello, but we quickly realized it was a distress call. Peter cautiously steered Lillian out of the channel towards the scene. The man in distress was named Cesar. He was to be our introduction to the Chantier Naval des Iles, where we were to spend the next two weeks.

Cesar is thirty something, Brazilian, energetic, quick to smile, and strikes me as the type of person who jumps into any project with both feet. Cesar had built the skiff in which he now stood frantically waving his arms. He had been taking her on her maiden voyage with an outboard motor he’d borrowed from CNI. During the test drive, the engine had fallen off into over a 100 feet of lagoon water. He didn’t have any oars and the wind was blowing hard.

We approach and threw him a line. With his skiff in tow, Cesar joined us onboard. He kept shaking his head at the reception he would receive upon his return. We commiserated with him on his misfortune. Given the depth in the lagoon, retrieving the engine seemed impossible. We marked the spot on the GPS and offered to tow him the mile or so to CNI. For us, it was nice to have someone to guide us into the yard.

But, our fortune was about to change as well. With less than a quarter mile to go to CNI, our own engine suddenly began to vibrate. The tachometer dropped precipitously to 600 rpm, well below the normal 1700. Simultaneously, the cooling water expelled out an exhaust port in the stern became intermittent and the engine temperature rose rapidly, indicating a saltwater pump failure. Under the threat of damaging the engine, we needed to shut down immediately. Cesar quickly directed us to the owner’s mooring, less than 100 yards away. We secured Lillian as quickly as possible and turned off the key.

Once moored, Peter, Cesar and I rowed into CNI. As we neared the dock, Cesar sheepishly called out, in french, that the engine had fallen in the water. The reply that came back was “Encore?” (Again?). It would seem that Cesar is a man of mixed fortune. Within the next few days, he would attempt to retrieve the outboard, only to have the rented dive boat capsize and half the scuba gear join the missing motor at the bottom of the lagoon. It was only by the end of the second week that Cesar’s enthusiasm and persistence would pay off and he would recover both the engine and the scuba gear.

In the meantime, however, I was beginning to feel as if we had entered our own twilight zone of misfortune. Our water pump had failed completely, spewing saltwater throughout the engine compartment. As a result, it had caused an electrical short in the alternator used to charge the batteries. Smoke would rise when the batteries were turned on. Now Lillian had three critical failures, no water pump, a frayed shroud, and a shorted alternator. She had no propulsion, limited electrical power, and no way to run the refrigerator. Instead of a trip to Bora Bora, Kay and Matthew were looking at a Spartanical week in a busy shipyard with the silhouette of Bora Bora mocking us on the horizon.

Looking back, our bad luck was actually fortuitous on many levels. Most critically, the engine pump could have failed in mid-ocean, instead of within gliding distance of a repair facility. A week and a half later, by the time Cesar had recovered his equipment, Lillian would have a new water pump, a rebuilt alternator, new fuel and oil filters, a new shroud, fresh oil, and a tank full of diesel. She would be ready to cross the ocean again.

Meanwhile, Kay, Matthew and I took advantage of the time to take scuba lessons. And, so as not to miss Bora Bora, the three of us took a ferry over to the island. While we were in Bora Bora, Peter stayed behind and got to know the cast of characters at CNI better, if only for a week. He said drinking beer with the yard crew on Friday after work reminded him of the lumber yard back in Idaho, except they spoke French.

Along with the blue collar crew at CNI, there is Violetta, who manages the front office. Perhaps the most beautiful woman we met in French Polynesia, Violetta is also, no doubt, the best dressed woman in any shipyard in the world. Despite her beauty she seemed to have a shyness and vulnerability about her. Sympathetic to our predicament, she helped us at several turns, especially with regard to the red-tape we needed to get parts cleared through customs, not to mention use of the laundry.

And, last but not least, my favorite person at CNI is George. At least three times a day I would search the yard looking for George seeking guidance or help. I’m not sure what his official position is, but he seems to be into everything: sanding hulls, repairing motors and alternators, supervising the placement of boats into dry dock, etc., etc., etc. When I would eventually find him in some corner of the yard, George would always respond as if he were glad for the interruption. With a very French shrug of the shoulders, wave of the hands, and a smile, he would give me an answer on the spot, or promise to come out to Lillian to have a look. It was George who ordered the shroud, rebuilt the alternator, installed the new pump, and fixed several other nagging problems.

While I wouldn’t go so far as to say that I look forward to Lillian’s next breakdown, being in need of help is one way to interact with people you would otherwise never meet. When all boat systems are operating, it’s very easy to go from anchorage to anchorage with your life centered around the boat: snorkeling, cocktails at sunset, a nice view of the sunset on one side and an island on the other. Having to repair the boat forces one to go ashore and seek help. After a week of boat problems, the yard of CNI and its good people were starting to feel like home.

Finally, however, our list of problems was resolved. Kay and Matthew had already left for the States, and after thirteen days since we first saw Cesar, Peter and I backed off the CNI mooring. As we motored out towards the pass in the reef, we looked back towards the dock to see Violetta waving her hands over her head. This time, it was neither a “Hello,” nor a call for help, but simply “Au Revoir.”