Last Leg

Last Leg

Late Entry

Oct 22, 2022

The Lillian B sailed into her home port of Rockport, Maine on June 25th, 2022, five days and a year since having departed on the Summer Solstice, 2021 bound for Scotland.

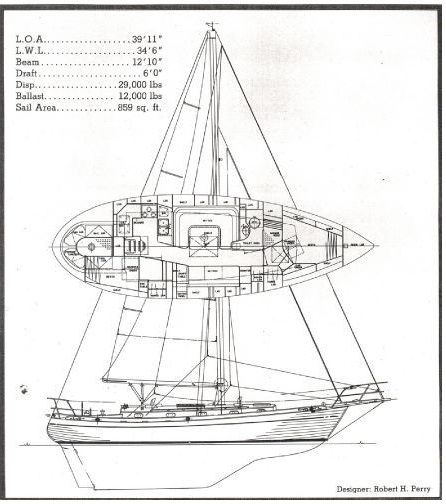

For me, the last push from Bermuda to Rockport was primarily about counting off the miles and getting the boat home. Assembling the crew for the trip was again uncertain in the time of COVID. The boat had spent the last month in waiting at Caroline Bay Marina in Bermuda. Meanwhile, I had returned to Alabama with a flight scheduled from JFK to Bermuda on Wednesday morning the 15th of June. At that time, Bermuda still required a negative COVID test 48 hours before departure. Driving from Alabama to JFK, my wife and I stopped at a Walgreens somewhere in Virginia for me to take a judiciously timed COVID test. A positive result would have created a whiplash effect on everyone’s travel plans. Fortunately, all crewmembers would test negative, although there was a concern when Brimmer Sherman’s flight was delayed, technically placing him outside the mandated 48 hour requirement. As it was, he and his stepson William Hill Harman (Hill) flew together into Bermuda that same Wednesday and found their way across the island to the Caroline Bay Marina. David Carstens, the fourth crewmember, would fly in just in time to head out to sea.

Looking north from Bermuda, Maine lies less than 750 nautical miles away. At a conservative estimate of 100 nm per day, that placed us approximately seven sailing days from home. As you might expect, preparing for a week’s sail is much less involved than for an ocean crossing. Meal planning for three weeks at sea requires some thought. Meal planning for only a week, with four crew members, was relatively easy. Each of us was tasked with planning for only two days of meals, with fresh produce available. David e-mailed his shopping list ahead and part of Thursday was spent pedaling the on-board folding bikes back and forth to a nearby grocery store.

Restocking food could be done on bicycles, but not so refueling. Lillian’s internal fuel tanks were nearly topped off with 72 gallons of diesel, but the 5 jerry cans on deck were empty. 72 gallons of fuel conservatively translates to over 280 miles of motoring, nearly 40% of the distance to Maine. Given that Lillian B. is a sailboat, it was tempting not to bother to fill the jerry cans, but tempting fate is a risky business, no matter how unlikely it was that we’d need that extra fuel. The Caroline Bay Marine does not have a fuel dock, but they have as friendly and supportive a staff as any marina in the North Atlantic. Their facility manager, Vincent Lightbourne, answers the phone with the line “how may I help you,” and he lives that attitude. And, Colin, dockhand and jack-of-all-trades, offered without hesitation to load the jerry cans into the back seat of his car and help refuel at a local gas station.

Middle: Vincent Lightbourne (Manager of Caroline Bay Marina, Bermuda)

Left: Burke Munger, Right: David Carstens (The crew that helped sail Lillian up from St. Maarten)

By Thursday evening the boat was restocked with fuel and food and ready to sail. The next morning, we backed out of the slip at Caroline Bay Marina with a wave to Vincent and Colin and began motoring through the well-marked channel over to St. George, the official port of clearance for boats entering and leaving Bermuda.

After dropping anchor in St. George harbor, the plan was to rendezvous with David and his seabag at a bar next to the bridge to Ordinance Island and then process out that evening for an early morning departure. The first part of that plan went well, but the plan to clear-out a day early … not so much. Unlike most of the other countries visited around the Atlantic, Bermuda does not allow clearing out the day before. Given that, I offered to row in Saturday morning, complete the paperwork, row back to the boat, and then we’d head out. The customs office opened at 7am and this would only delay our planned departure by an hour or two. This suggestion was immediately rejected. I was informed in no uncertain terms that I’d have to bring Lillian into the dock to retrieve the flare gun that I’d relinquished upon arrival. I thought to myself that the gun probably was too old to even fire. I shrugged my shoulders and suggested that they could kept it. That suggestion was not well received. The custom officer angrily accused me of disrespecting the laws of Bermuda. To my mind, it wasn’t disrespectful, it just didn’t make sense on the one hand to trust a boat captain to surrender a flare gun upon entry but on the other, not trust him or her to row it back to the boat on departure. Fortunately, before I had time to generate a beer inspired argument, the crew literally stepped in and reassured the agent that we would bring the boat to the dock in the morning. In hindsight, the officials of Bermuda deserve credit in being both conscientious and rigorous in their enforcement of Bermuda’s no-weapons policy. The next morning we brought Lillian alongside the customs dock and the customs agent handed me the flare gun and then she walkout out with me to dockside and watched very closely as we cast off. Notice to mariners, if you visit Bermuda and have anything that qualifies as a weapon, such as flares and spear guns, they will take it seriously. In any event, by 9 am we had received clearance from Bermuda Radio to depart St. George and by 10 am we were clear of the reefs around the island and were pointing Lillian due North.

Seven days later we would be sitting on a mooring in Rockland, Maine waiting for clearance into the US. The trip would have been just another week at sea if it hadn’t been for the addition of Brimmer’s stepson Hill to the crew. Hill was a first-time bluewater sailor who brought uncontained enthusiasm to the passage. The trip introduced him to a range of sailing conditions. It was as if a full gamut of experiences had been planned for his bluewater introduction. For the first two days we had the wind and waves from dead astern. This was typical of the wind direction Lillian had experience for much of her circumnavigation of the North and Mid-Atlantic, as she ran before the trade winds. While that sounds ideal, wind and waves from astern has the disadvantage of confusing the sails. The waves rock the boat from side to side and threaten to flip the main sail from port to starboard, or from starboard back to port. In such a case, we choose a side and then lash the boom over using a line known as a preventer. The sail will occasionally start to flip over, but the preventer holds it to one side until the boat rolls back. With the wind behind him, Hill averaged over 6.3 VMG (Velocity Made Good)* on his first watch Saturday evening, June 18th. That would match the best VMG of the entire crossing and if we’d been able to sustain it, that VMG would have put us into Maine in only 5 days. But the conditions were about to change.

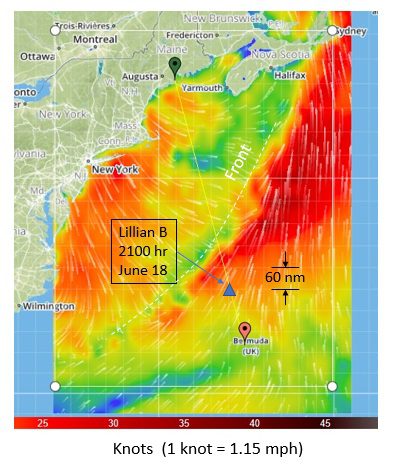

When I took over Hill’s watch at 9pm, the wind was still out of the South, but the evening’s Predict Wind weather map downloaded via satellite indicated that a dramatic shift was on its way. There was a cold front rapidly approaching from the northwest. It was still over 100 miles away, but bright flashes of lightning could be seen illuminating the night as they danced up and down the front.

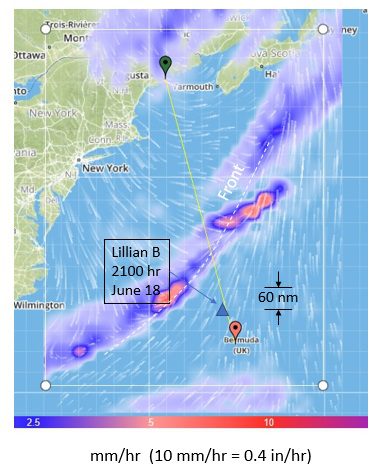

Wind predictions at 9 PM, June 18 (Predict WindTM)

In preparation, I went below and closed all the hatches and put on my foul weather gear. The next step was to inspect the deck and rigging to make sure everything was secure, including the jerry cans and the inflatable dingy strapped to the foredeck. The main sail was then reduced to two points of reef and the large Genoa was furled and replaced with the smaller, much more manageable staysail. With those preparations complete, I settled into the captain’s chair and softly challenged the lightshow to the northeast to bring it on. Perhaps it was foolish to challenge mother nature but, rigged as she was, Lillian could handle any bursts of wind that the front might bring. As for lightning, I take comfort in the delusion that her grounded mast would leak off any build-up of charge with a display of Saint-Elmo’s fire, thus preventing a direct strike. Fortunately, that theory was not tested and by the time I turned over the watch to Brimmer at midnight the front had weakened and the lightening strikes greatly diminished. It wasn’t until the next morning, when Brimmer turned over the helm to Hill, that the front would pass directly overhead, dropping torrential rains on Hill and the boat. The log entry at the end of Hill’s watch would read, “ Nearly an inch of rain in twenty minutes.”

Rain predictions at 9 PM, June 18 (Predict WindTM)

For the next two and half days, Hill would be introduced to the experience of sailing close haul, with the wind and waves coming at the bow. The winds had clocked around to be from north, such that the boat could no longer head directly towards Rockland but had to sail off at an angle. We could no longer measure the speed of the wind, since the wind indicator had stopped working back in the Caribbean, but we could judge its strength by the boat’s response.

On Monday morning, Hill logged in the top speed of the passage at 7.3 knots. That speed is close to the maximum hull speed of the boat, although the VMG was only 6.33 because the heading was 15 degrees to the left of due north. The sail configuration Hill had inherited from the previous watch was 1 point of reef in the main sail with both the staysail and Genoa fully deployed. The Genoa is the most effective sail on Lillian for sailing close haul. The main sail had been reduced because the winds, whatever they might have measured, must have been brisk. With a stiff breeze, reducing the main sail does not slow the boat down, but does balance her better, reducing the weather helm, i.e. the tendency for her to turn into the wind. Conversely, the addition of the staysail in parallel with the Genoa does not speed her up. While open for debate, having two headsails is less efficient than using just one. Unless perfectly trimmed for the wind conditions, they will interfere with each other. This is why one rarely sees a biplane. What deploying the staysail does accomplish is to take some of the load off the Genoa …. plus it looks very nice for anyone passing by out in the middle of the ocean. Given her sail configuration, wind direction, heading, and speed, Lillian must have been powering through the ocean with her starboard side rail touching the water. Hill’s entry at the end of that sunrise watch was “BANG**! … POW !!!.”

Heeling over with Hill at the helm, powering along at 7+ knots

By noon on Tuesday, the next day, the winds had died down to the extent that we started the engine and motored for 15 hours until the winds switched around to come from out of the east. We were now 300 miles from the official port of entry, Rockland Maine. The next three days were idyllic sailing with steady winds and clear, sunny skies.

The climate was changing. At the end of each watch we record the air and water temperatures. Off Bermuda the air and sea temperatures were a warm 84 F and 77 F respectively. On Wednesday morning, 300 miles from Maine, David Carstens recorded the air and water as 75 F and 74 F. Twenty four hours later, the seawater temperature had dropped 18 degrees to 56 F and the air temperature was down to 69 F. We had crossed out of the gulf stream that angles abruptly out to the east at Cape Cod. We were entering the Gulf of Maine and the last two night-watches would be in warmer gear.

Parkas come out for the sunrise watch

In the dark hours of the early morning of our last full day at sea we would be treated to the lights of the large fishing fleet working the sea canyons off the east coast . These were the fishing grounds described by Linda Greenlaw in her book, “The Hungry Ocean.” From a distance, the fleet was a mesmerizing string of white lights, strung out across our path. From far away it looks as if we would have to carefully navigate between them, without knowledge of how much distance was needed to stay clear of their lines. Fortunately, once in line with the fleet, it became evident there was plenty of room and we crossed without incident and with a new respect for fisherman.

AIS displaying the fleet on the chart plotter

That crossing of the fleet was not the last special event in store for Hill’s bluewater introduction. Both Hill and Brimmer are avid birdwatchers who, through out the week would excitedly identify the variety of bird that fly out over the ocean. Fortunately for them, the one obstruction that sat squarely on our direct course between Bermuda and Rockland was Matinicus Rock, 15 miles off the coast of Maine. Matinicus is a breeding ground for Puffins and a sanctuary for a host of other birds and marine life. Even though we were eager to get to Rockland before sunset, we did a loop around the island instead of passing it by, then transitioned to full delivery mode. With the main sail and Genoa fully deployed and the engine helping out at 1500 rpm we dodged lobster pots and averaged 7 knots to arrive in Rockland harbor just in time to pick up a mooring in the fading light.

Birders Hill and Brimmer watching out for birds off Matinicus Rock

The next morning we cleared customs over the phone and then motored the six miles over to the town dock in Rockport. It seemed somehow appropriate that Brimmer Sherman, David Carstens, and I, with the addition of Willian Hill Harman, were the same crew that had set out for Scotland the year before. As we tied up at the dock, Brimmer and Hill were met by family members who had just arrived from Alabama to greet them. Dave would have to wait several days before catching his fight home to rendezvous with family. And for me and my wife Kay, summer in Rockport passed by with so much activity that only now did I find the time to write this entry.

The circumnavigation that had been inspired by a pre-COVID suggestion to sail over to the wedding of my niece Sally Poole Hill in Scotland was complete … although the wedding plans would change due to COVID and we never made it to Scotland. The voyage was occasionally fun and always an experience. At some point, I plan to write an epilogue in an attempt to sum up that experience, but that will take some thought. In the meantime, a sincere thank you to everyone who made the journey, whether virtually or as crew.

*VMG (Velocity Made Good) is the speed in the direction of your destination and, in that sense, is a better indication than speed alone of one’s progress. One can be going very fast, but if it’s in the wrong direction, it doesn’t help get you where you want to go.