Take the Weather Report with a Grain of Sea Salt

Thursday August 09, 2014 (74o 35’No 90.00’W): Rigby Harbour,

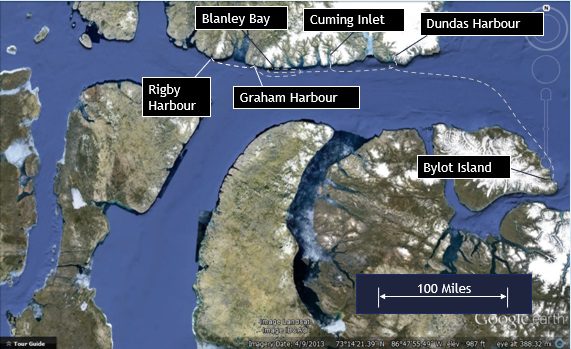

Graham Harbour was a safe anchorage, as hoped, but during our three day stay it was still necessary to re-anchor nearly a dozen times due to wind changes and the roaming pieces of ice that had found their way into the inner harbor. Like the other bays, inlets, and harbors on the south coast of Devon Island, the surrounding cliffs continue their steep descent into the water, leaving little shallow ground for anchoring. For good holding, it is best if the sea bottom is no more than 30 feet deep and flat, with a seabed readily penetrated by the anchor.

At Graham there was a shoal at the head of the harbor created by the outflow of the river but it dropped off steeply, such that a shifting wind could blow the boat back aground. Anchoring at the harbor head was good in a north wind but not when the wind swirled around from the south. At the other end of the harbor was a slightly better shoal but it was a favorite spot for wandering ice. While in Graham Harbour, Lillian touched land at least four times. Fortunately the bottom is soft, consisting of loose shale, kelp, and mud. Bumping against the shoals, the shifting of the winds, and the movement of the ice was not particularly threatening, but it was an annoyance that prevented us from being able to fully relax.

Despite the aggravation of repeatedly have to move the boat, we were grateful to be in a secure harbor and were biding time until the ice reports showed it was safe to head further down the coast. On our third day in Graham (Friday, Aug 8th ) the weather report and ice observations came in around 5 pm. The ice chart showed it was clear water down to Rigby, and the weather report was good.

“Weather Prediction:

Issued 05:30 AM EDT 8 Aug 14 for Today, Tonight and Saturday

Lancaster western half:

Wind – Wind northeast 25 knots diminishing to northeast 15 late this morning and to light late this afternoon. Wind increasing to north 20 late this evening then diminishing to north 15 Saturday morning.”

Twenty five knots is a comfortable wind for Lillian and the direction was favorable. As further encouragement, we received the following message from Manevai, saying that they were at Rigby and conditions were good. (The message was a day old and Manevai would have moved on from Rigby by the time we finally arrived.)

“Hello Lillian B,

I got your email address thanks to John. We arrived in Rigby bay (where we still are) yesterday morning. Pleasant and safe anchorage with correct holding (much better than Maxwell Bay or Blanley). No ice at all inside. … Eric, Manevai”

Within less than fifteen minutes after receiving the above reports, the boat was secured, the anchor was up and we underway to Rigby, thirty miles to the west. Under full sail we cut through bits of widely scattered ice and then passed within a mile of an island of ice, at least a mile in diameter. Pete pointed out with excitement that it had a polar bear, running hard across its surface.

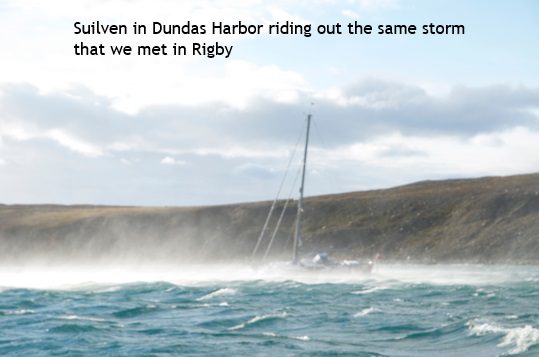

As we sailed west, the winds strengthened throughout the afternoon, contrary to the weather predictions. By the time we were within one mile of the mouth of Rigby Harbour, they had increased to a steady 30 knots, with gusts to 40. We were already running on a reefed mainsail. Looking over to the north shore, Dave spotted the water equivalent of dust devils, small tornadoes of mist sweeping across the water off the base of the mountains. “Let’s get the main down,” he recommended. Relying on the engine to turn into the wind, the mainsail was dropped and the genoa roller reefed. Ten minutes later, we rounded up into the entrance to Rigby Bay under power to be met by 50 knot winds out of the north. The harbor was two miles deep. Combined with the wind, the waves building over that short fetch made it nearly impossible to make headway without straining the engine. With little choice, we retreated back to the partial shelter of the cliffs east of the entrance. There, with smaller waves, it was possible to hold our position at a reasonable 1500 rpm.

For an hour we took turns keeping the bow into the wind, going neither forward nor backward. Looking ahead into the storm, lines of spray would rush toward the boat at fifty knots, giving just enough warning to be able duck for cover below the level of the dodger as cold wind and spray flew over the cockpit. The inflatable Zodiac lashed to the fore-deck would become partially airborne at each gust and the canvas “lazy jack,” that normally serves as a cradle to stow the mainsail, was itself acting like a sail. Going forward, we snugged the Zodiac to the deck and tightly lashed the mainsail to the boom with short lengths of line. Aft of the cockpit, the folded canvas Bimini was completely removed and stowed hastily below.

With the boat’s wind resistance reduced, we headed back around the point for another attempt to enter Rigby Bay. At a safe 1700 rpms, Lillian was able to keep her nose to the wind and move forward in only incremental gains, but forward none-the-less. Each tiny step towards the head of the harbor meant that the waves were imperceptibly smaller, the resistance less, and the speed a split fraction of a knot faster. Slowly we were making progress. At one point, Pete recorded a gust of 67 knots (74 mph) on the wind gauge, making us wonder where we missed “hurricane winds” in the forecast.

Despite the seemingly relentless winds, after an hour of battle Lillian was now gaining ground at over 3 knots. After another hour, with 50 knots winds funneling down the valley at the head of the harbor, we began searching for a secure place to anchor. Back in Maine, the solution would have been to look at the contour lines on the chart plotter and picked the best location. In the arctic, contour lines are non-existent and the charts dangerously misleading. Back at Graham Harbour, with 30 feet of water under our keel, the chart indicated we were 100 meters on shore. The converse could have as easily been true. In this regard, the Forward Looking Sonar (FLS) has proved invaluable. It provides a graphical output of the depth out several boat lengths in front of the bow. Using the FLS as a mapping tool, we motored back and forth across the head of Rigby Harbour looking for a suitable spot. As with the other harbors, Rigby is deep and then shoals rapidly. Within two boat lengths the depth typically changes twenty feet. In order for a boat to hold in strong winds requires a scope (the ratio of the length of the anchor line to the depth of the anchor) of 3 or more for an anchor line made of chain. Once the anchor is dug into the bottom, the higher the scope, the stronger the holding.

Two attempts to drop the anchor in twenty feet of water failed. The technique for anchoring is to motor head to the wind to the drop point, drop anchor, and then pay out chain rapidly as the boat moves backwards and the anchor digs into the seabed. If the chain is not laid quickly enough to establish sufficient scope or the boat is moving too fast, the anchor doesn’t grab hold and, in the case of a steep slope, is quickly dragged into water too deep to anchor.

On the third try we used the engine to approach as close to the shoal as we dared without running aground and dropped the anchor with the sonar reporting eight feet of water. (Lillian draws slightly over six feet.) With the wind pushing the boat back hard, Pete and Dave disengaged the clutch on the windless and let the chain run out in free fall, plunging as fast as its weight would take it. At the same time, I did my best to keep her nose to the wind and her retreat below half a knot. After dispensing nearly 175 feet, the end of the chain was made fast and we watched with relief as the bow was pulled abruptly around into the wind, like reigning in a horse. Lillian began swinging from side to side on the anchor, as she would do all through the rest of the storm and the next day without slipping as much as an inch.

Once again, we had dropped anchor around 2:30 in the morning in the light of the Arctic summer. Instead of going straight to bed, we poured ourselves a drink and stayed up to enjoy the sensation of being securely anchored in a storm, reviewing the details of an unexpectedly challenging and exciting day (nearly forgetting in the aftermath of the storm the excitement of seeing a polar bear) and appreciating the knowledge that the boat could take 50 knot winds in stride.