Home to Alabama

Late entry, May 13th, 2004

Atuona, Hiva Oa

On the morning of May 13th in Hiva Oa, Marquesas, after having crewed on the Lillian B. from Stuart, Florida, down to Jamaica, through the Panama Canal, over to Galapagos and on to the Marquesas Islands, Dick Hiatt began the long journey home to Alabama. By first light he had already finished packing his bags; he and I had rowed to shore; and we were walking up the steep grade to the airport, with two heavy pieces of luggage trying to hold us back. Fortunately, as is typical of Marquesian hospitality, a truck stopped before long to offer us a ride the remaining 10km to the airfield. We arrived at the terminal three hours before flight time. Tahiti Air on Hiva Oa is an open walled building with the minimum of accoutrements needed to run an airline: scales, ticket counters, restrooms, aircraft tugs, fuel barrels, emergency equipment, etc. The only custodian was a skinny orange cat who came up to rub against our legs. Dick was dressed in long pants, a flowered shirt, and a straw hat; ready to travel. With no one there and a telephone ringing, unanswered behind a locked door, we were at first concerned that the flight had been cancelled. We were relieved when airline personnel and passengers finally began to arrive. The ticket counter was uncovered, the baggage weighed, an aircraft was towed onto the ramp, and the pilot began his preflight inspection. I stayed with Dick through his check-in. We said a quick goodbye and I then hurried out to try to catch a ride down the hill. As I walked towards the road, I felt a moment’s regret that I hadn’t been more explicit in letting him know how much Peter and I had valued his company on the voyage.

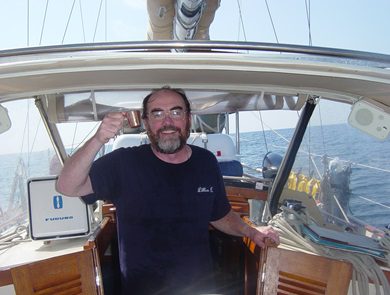

It is hard to write objectively about Dick Hiatt, as I’ve known him as a friend for nearly 25 years. Dick is not a sailor. Dick is not even very mechanical. If I were asked to select a single word to describe him, it would be humanitarian. As one of the founders of the Food Bank in Huntsville, Alabama, Dick has dedicated himself to improving conditions for those less fortunate. What Dick offered for a long ocean passage was the intangible of a longtime friend with a positive perspective on the world. With this in mind, I asked him early one morning, as we rode bicycles through our neighborhood in Huntsville, Alabama ride, if he wanted to sail to Tahiti. On a cold morning, with months to go before the departure date, the concept of sailing 3000 miles across the Pacific to a tropical island sounds reasonable, even sensible. He said he would have to first check with his wife, Suzie, and then with the Board of Directors of the Food Bank. That was all the answer I was looking for. Half a year later, Dick would board a Greyhound bus in Huntsville, Alabama, bound for Stuart, Florida where the Lillian B. and crew were awaiting his arrival. I joked with Peter about the imagine of Dick, sitting in the back of a Greyhound Bus, telling the passenger next to him that he was headed to Tahiti.

Upon his arrival in Florida, Dick’s initiation to sailing was immediate. The first two weeks of the trip were by far the most demanding sailing we have seen since leaving Maine. Through the Bahamas we had strong winds and twelve foot waves. We would take turns standing four hour watches at the helm, with no autopilot. Dick’s approach to sailing is cautious. Unlike Peter, who from day one would unhesitatingly initiate changes in sail configuration under high wind conditions, Dick would rarely make a move without first seeking advice. I was glad to see the two styles converge somewhat as the voyage progressed and as we all gained experience. By the Marquesas, Dick had come into his own on watch: reefing and furling sails on his own in response to changing wind conditions. But, despite his new sailing skills, I suspect that Dick’s favorite watches remained those where he didn’t have to deal with sail changes and could sit in the helmsman chair and enjoy the ride as he maintained an eye out for approaching ships.

While Dick would typically leave the sail changes to me or Peter, he was our advisor when it was time to operate the radios. In the Navy, Dick was a communication specialist. Without him, it is doubtful that we would ever have gotten the Single Side Band radio up and operating on board the Lillian B. Before leaving Huntsville, Dick had already researched the hardware and software we would need to send out e-mails. He helped set up the system and assembled a references library to guide us in operating the equipment.

One of the most memorable contribution of Dick Hiatt to the voyage of the Lillian B. was the rude awakening Kay, Matthew, Peter and I received the morning we were to cross the equator. Drawing on Naval tradition, Dick had us up before dawn eating hard tack and performing rituals as we transformed from “pollywogs” to “shellbacks.” He had us “kissing the baby’s belly” and providing offerings to Neptune, in strict accordance with thoroughly researched Naval (navel?) traditions that have evolved over centuries at sea. Having passed the test, we were presented with elaborate and colorful certificates commemorating and authenticating our initiation as Shellbacks.

Since returning home, Dick has kept in touch via the Sailmail link he helped set-up. He has written longingly about being at sea. This at first struck us as ironic, given how eager he had been to leave the moment we set foot in the Marquesas. Looking back, it is clear that most of the time Dick truly enjoyed the adventure. However, there were also times when the Lillian B. would lose him to homesickness. The “Old Warrior,” as nicknamed by an aged and weathered women on the beach in Jamaica, would sometimes lay listless on his bunk and stare at the ceiling. Dick missed home. He often talked about his wife, Suzie, and his daughter, Megan, in her first year at college. One of the emotional high points of the trip will remain Dick’s excitement at having Suzie rendezvous with him in the Galapagos.

After the Galapagos, was the 3000 mile passage of 23 days across the Pacific to the Marquesas. It would have been a tough trip without his help and company. But, by the time we first sighted the islands of the Marquesas, Dick was ready to get home to his family. His leaving would be a loss for both Peter and me. However, we couldn’t help but share his excitement when the day finally arrived for him to board an airplane and begin the long journey home.